All About Bloodroot

Posted By American Meadows Content Team on Apr 10, 2017 · Revised on Oct 3, 2025

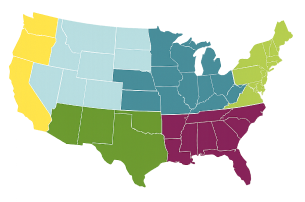

Knowing your location helps us recommend plants that will thrive in your climate, based on your Growing Zone.

Posted By American Meadows Content Team on Apr 10, 2017 · Revised on Oct 3, 2025

Bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis), a member of the Poppy family, is a true American native, growing naturally in deciduous forests across the entire eastern half of the USA and southern Canada.

And, by looking at the way it grows in the wild, we can learn how to grow this beauty successfully in our own gardens.

Each spring, after months of winter dormancy, the forests suddenly come alive. As the sun streaks through the still-bare branches of the taller canopy trees, it gradually warms the cold ground. And then something truly magical happens: a host of spring wildflowers - dog-tooth violets, trillium, spring beauties, Dutchman’s breeches, and many more - burst forth to light up the ground.

And among the very first wildflowers to emerge each spring is the beautiful Bloodroot

Each flower consists of 8-10 sparkling-white, pointed petals radiating out from the clear yellow center. Bloodroot grows naturally close to the forest floor. This is where fallen leaves and twigs gradually decay and merge into the top layers of soil to form a delicate nutrient-rich structure.

Nobody rakes leaves in the forest and the decaying leaves on the forest floor create the perfect environment for bloodroot.

The underground portion of each Bloodroot plant is actually a fleshy subterranean stem, called a rhizome. Bloodroot rhizomes grow outward, horizontally through the soft soil of the forest floor, eventually forming a substantial colony.

A carpet of flowers: Individual rhizomes are actually segmented by nodes, each of which can sprout a separate flower stalk. This results in a dense carpet of bloodroot flowers that emerge like magic among the decaying leaves of the forest floor.

On sunny days, the pristine white flowers open wide to receive the early-pollinating insects. But each night and on rainy days they close up tightly to protect their precious pollen.

After a few short weeks the trees of the forest leaf out, the ground becomes shaded, and the spring wildflowers begin to set seed.

Many woodland wildflowers are ephemeral, meaning that, after they have finished flowering and set seed, the entire plant becomes dormant and disappears below ground until the following spring.

Some, however--most notably Bloodroot, Jack-in-the-pulpit, and trillium-- continue to maintain their leaves during the summer for added photosynthesis.

Bloodroot leaves are wide and scalloped. These form an attractive groundcover that, especially in cooler parts of the country, remains above ground most of the summer.

Choose a location that offers similar conditions to those you find in our native forests:

Emulate the conditions you find on the forest floor:

Give your Bloodroot’s underground rhizome plenty room to expand:

And avoid these locations:

And finally, two words of caution:

What does the name Bloodroot signify?

If you cut or bruise a Bloodroot rhizome it exudes a red watery sap. Native Americans basket makers still extract this sap and use it as a dye.

When we first moved to Vermont, over twenty years ago now, each spring I took note of a solitary white flower that would appear among a profusion of ferns on the slope behind our house. A quick look in a wildflower guide told me it was Bloodroot.

Eventually I decided to clear the slope and create a brand new garden. First, in springtime, I carefully marked the location of the Bloodroot. Then the following fall I dug around the marker and soon discovered a single rhizome that exuded the characteristic red sap. I knew I had what I was looking for!

I then carefully replanted it in my newly created ‘shade garden’ beneath a trio of serviceberries. And each spring for the next several years I was delighted by the ever-widening colony of white Bloodroot flowers, to be followed later by the characteristic scalloped leaves.

After a few more years, once again in fall, I re-dug my Bloodroot. I carefully divided the tangled mass of rhizomes and replanted several segments in other parts of the garden. Now every April I look forward to the emergence of five beautiful colonies of this amazing wildflower, telling me once again that spring has returned to the mountains of Vermont.

About the Author: Judith Irven is an accomplished Vermont landscape designer and garden writer, and she delights in helping people everywhere create beautiful gardens.

To learn more about the plants we sell and how to grow them in your yard, garden beds and patio containers, sign up for our inspiring emails.